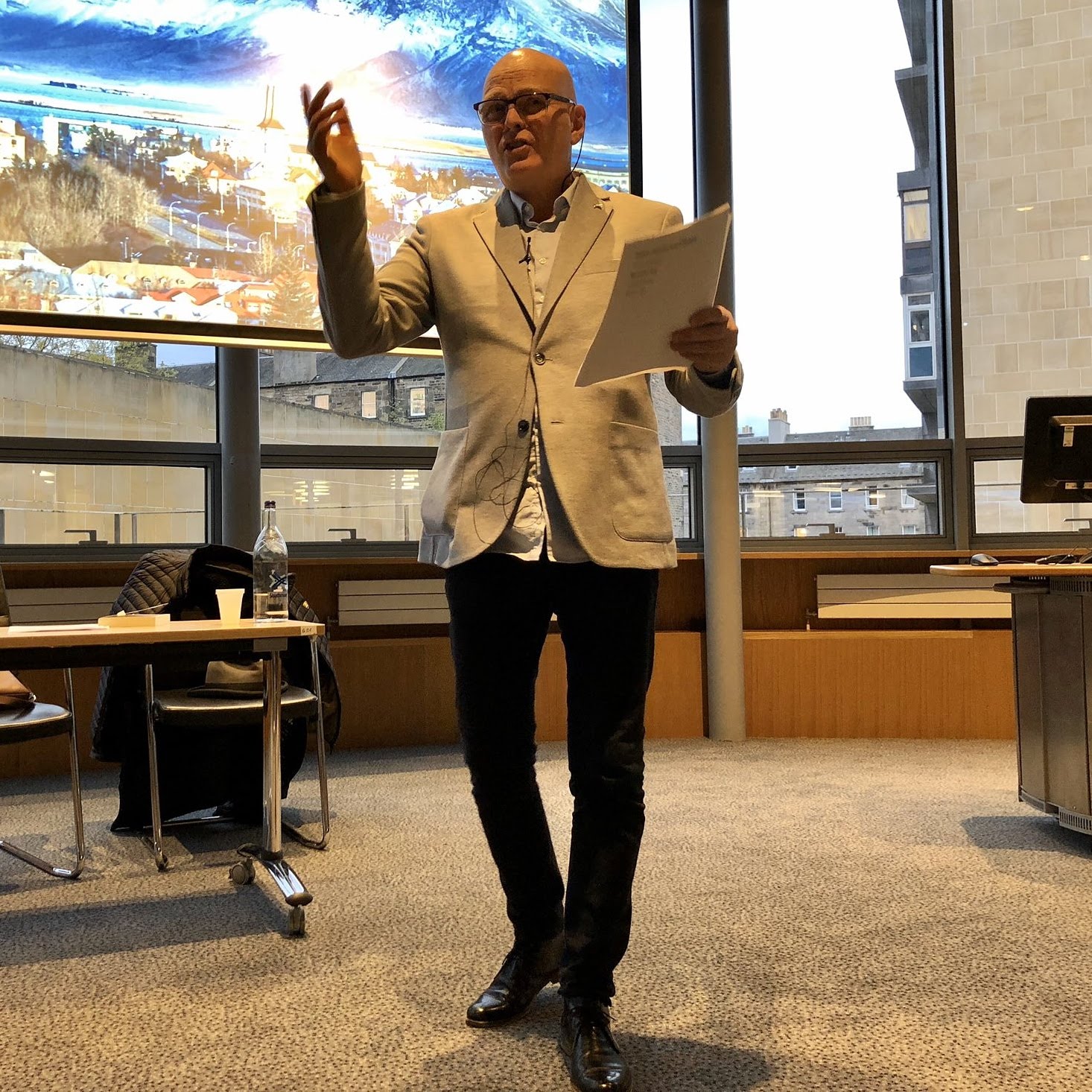

On 23 October 2019 Hallgrímur Helgason gave a lecture at a conference titled ‘Nordic Branding and the Reception of the Nordic Model Abroad’, held at the University of Edinburgh. The conference was chaired by Mr. Alan Macniven, Head of Scandinavian Studies, Department of European Languages & Cultures at The University of Edinburgh. Hallgrimur’s text appears below.

Hallgrímur Helgason

The Icelandic Tradition of Silence

In the summer of 1972, when I was thirteen years old, I traveled to the States for the first time, to visit my uncle and his family in Larchmont, a suburb of New York City. His sons introduced me to their friends from the neighbourhood and the American boys had a hard time with my name, Hallgrimur, or as we say in Iceland: Hallgrímur.

“We’ll call you Johnny,” they said. And a couple of days later, after they hadn’t heard me speak a word in their company, they added the last name Silent. So for three whole weeks my name was Johnny Silent.

It stuck with me. I sometimes think of it.

Because in this way, I was a rather good representative of my country and my culture. We were a silent bunch. The summers leading up to 1972 I had spent on farms, north and south in Iceland, doing my bit as a child labourer, as was the custom in those times, when farmers always needed a hand with milking their cows and making their hay. And some of those farmers went through three months without speaking a word to us other than “Rise!” or “Lunch!”. I mean, they spoke more to their dogs than us, the working kids. And to their own family they never said a word. (It was mostly hm? or hm.)

In the early eighties our TV-people even discovered an eighty year old farmer out west who had not spoken a single word for over 50 years, not since his girl left him for his brother. He had been living alone on a very remote farm and when they interviewed him, the language he spoke was so hard to understand, that his words had to be aided by subtitles in our own language.

The age-old tradition of silence spilled over to every aspect of our society. If there was a problem within the family, people shut up about it, no matter if it was sexual abuse, adultery, bankruptcy, homosexuality, or an alcoholic problem. No one spoke about it. People went to their graves

without asking who it really was that conceived them. Many wives silently endured an abusive husband, children grew up with carrying heavy secrets inside them. In the political field all possible scandals were silenced, and as a poet you gained the most respect if you did not publish a book for at least twenty years and never gave interviews. Speaking was considered a weakness…

Oh, how badly I fitted into this tradition…

Text-People

Yes. We were not just very good with words. Except on paper. Because our big national tradition, beside the cult of silence, was literature.

I will now read a short chapter from my novel, The Woman at 1000 Degrees, addressing the Icelandic tradition of silence.

So you get my drift. We were non-speaking text people, people who read and wrote, but hardly ever spoke.

We were so set on silence that when we discovered America in the year 1000 we did not tell anyone about it.

So for us, to see Columbus come along some 500 years later, and claim that he had discovered this amazing continent, was a bit like for Leonardo da Vinci to witness the Wright brothers’ first successful airplane.

“I told you, guys.”

I mean, we could have colonised Greenland, Canada and the rest of America, we could have become an empire, but at the time there were only three people living in Iceland and they were not on speaking terms.

We even wrote the first novels of Europe, called the Sagas, great and

classic works of literature written in the 13th century, but we kept them to ourselves. They were not translated into other languages for about 700 years. The big and beautiful Penguin edition of “The Sagas of the Icelanders” dates from 2001.

When I was at primary school, aged ten, and had to study Danish, we were only taught the grammar and the vocabulary, we never had to speak it, it was as if they did not expect us ever to use it, for we never learned the pronunciation. And learning Danish without the pronunciation is like learning to swim in a pool without water.

I mean, they only taught us language on paper. We were a nation of readers and writers. We were text-people. And we still are.

Still to this day, every single Icelandic person who passes away, gets his or hers obituary in the paper. Some friend or someone from the family writes a small piece remembering the dead one, people feel obliged to do it, for in a society fixed on text, if you don’t get an obituary about yourself, it’s as if you never really existed. In the olden times it was the church that was responsible for keeping records of all people alive. And before the church it was the Sagas. As a result, we have written records of ALL the people who ever existed in our nation’s history.

We are text people.

In an interview last week, our biggest DJ made the interesting remark that throughout his career he has noticed that Icelanders do not dance to the beat but the lyrics. Rather than move our bodies according to the rythm, we simply tend to jump around shouting the lines we know. We are text people. Silent and stubborn-dancing text people.

Literature as Religion

And for the text-people literature is religion. We came late to Christianity and some say we never really got it, but literature has been with us from day one. I mean, we preserved and wrote down the mythology and poetry of the Vikings, this is called the Poetic Edda, and we also wrote the histories of the Scandinavian kings, and then we wrote the Sagas, the first European novels, rather shortly after settling in Iceland.

The Sagas are our Bible, we refer to them almost every day, their characters are living legends, our role models and swordbearing saints, and people are still debating their marriage feuds, their hero status and what they were thinking when they said this and that. When I read the most amusing chapters for my kids they can’t stop laughing. It’s got such force of life. And only last week, I was at a symposium in the north west of Iceland. One of the farmers out there told me he reads Niall’s Saga (the best of them all) once a year. By now he has read it 44 times. And he’s still able to see new sides to it. Another farmer started arguing to me that the “bad guy” Flosi, at the end of Niall’s Saga, was wrongfully presented in the book, the author hadn’t got him right. “For Flosi was not a villain. He could never have said this.”

This particular Saga was written in 1270.

It’s very much like theologists debating the emphasises of the various gospels.

So being a writer in a land like this, is simply great of course. People still care about literature. I live in a writer’s paradise. I get a monthly salary from the state for being a writer. And every time I walk into a bar, someone comes up to me and wants to give me a story or a character. “Hey, did I ever tell you about my uncle Elli, he lives out east, he’s totally crazy. You have to put him in your next book! Let me buy you a drink.”

Iceland is like this big literary workshop with free drinks for the writer. And this comes from tradition. The Sagas are not by any specified authors, we do not know who wrote them, they were collective works of art, like the catholic cathedrals. The Sagas were written by the Icelandic people.

From Shyness to Loudness

But… things are changing. For instance, I can tell you that by now we have broken our silence, which is not so bad at all.

The best indicator of this is football. I remember in my youth, when the national team played at home in Reykjavik against Scotland, Norway or someone else, people just sat there in the stands and watched the game without making any kind of noise, like they were attending a state funeral, which they were, in a way, since we always lost… At most we grumbled to ourselves. (“He shouldn’t be on the team this one…”) Only when we scored, people cheered (this only happened once every five years).

But when you go to those games today, the picture is totally different. People are shouting and cheering for the whole 90 minutes. Icelandic football fans have even become known all over the world for their energetic singing and chanting, as well as their famous viking clap. “Tapp tapp, Húh!”

In just my lifetime we have learned to make noise, we have learned to express ourselves, in just my lifetime I have seen my nation learn to speak.

Another example of this is our radio. Back in the seventies we only had one radio station that played Bach and Mendelssohn all day long, and nobody went on air without a well prepared script, everything in our culture was scripted, stiff and official, adorned with silence. But today we have countless stations with talking heads blabbing away all day long, and drunk people calling in from their jacuzzis.

I’m not sure which scenario is better, but what remains clear is that the Icelandic nation has really forsaken it’s age old tradition of silence.

How did we find our voice?

So what happened? How did we find our voice?

I think the main reason is that we finally came in contact with the world. We saw how other people went about in their lives, and how strange our behaviour was. You have to remember that we were an isolated remote island for a thousand years, with only two ships coming each year, one in spring and one in fall. Interestingly enough they were called “The Spring Ship” and “The Autumn Ship”. Imagine the patience we had to have.

“I thought you were going abroad?”

“Yes, but I missed the spring ship. I will go in the fall.”

Today we have at least fifty airplanes leaving Keflavik airport every

single day. Our isolation was broken in the beginning of the last century but it took us a hundred years to break our silence.

Living With Your Parents…

Another factor was independence. We had been a Danish colony for most of those dark and dreary one thousand years, but in 1944, we used the opportunity, when the Danish king was under German rule, to break free. We got our own flag, our own national hymn and our own president. And with time we got our self-esteem.

Financially and militarily it might be easier to be a part of someone else’s kingdom, but it’s a mixed blessing, it’s like living with your parents. You get all the meals and washing but you don’t really grow up. (Do you hear me, Scotland?) You are not the master of your own life. In 1944 we became our own masters, sort of… not quite, since at this moment in time we were occupied by our American friends. It was during WW2. And after the war we got so worried that the Russians might overtake us, that we asked the Americans to stay. And stay they did, for sixty years, all the way until 2005, when Bush junior needed all his men in Iraq, and they closed down the US army base in Keflavik.

So in 2005, for the first time, almost since the Age of Settlement, we were on our own, finally and fully independent in name and reality. And it only took us three years to ruin it all, for in October 2008 came the financial crash and Iceland was practically bankrupt. In the years leading up to it, we had behaved recklessly, we were too greedy, too impatient, and partying too hard. Very much like teenagers who have just moved out of their parents house. The International Monetary Fund had to move in and help us back on our feet.

So I tell you dear Scotland: When you do move out of Buckingham Palace, don’t go straight to the bar. Not in a hundred years or so.

Spiritual Climate Change

But there are clouds on the horizon for Icelandic culture. We have seen some difficulties and drawbacks in our journey from shyness to loudness, from silence to independence to global recognition.

In “The Saga of Gunnlaugur Serpent-Tounge”, which was probably written around 1260, the main character, the poet, travels around the British Isles, and wherever he goes, he can recite his poetry. He’s like a rapper on tour, and everybody can understand him, except for a few provinces in Ireland, where they spoke Gaelic. It seems that the Old Norse language and Old English (or Anglosaxon) were so similar, that people understood each other, or that the cultural influence of the Vikings was so great that they even managed to occupy the language as well as the territories.

Today we face the opposite, of course. The cultural influence of English is about to change our language, the latin of the north, for good. The younger generations also seem to have totally stopped reading by now, they are glued to their phones 16/7 (16 hours a day), relying totally on computer games, Netflix and illegal streaming and downloading. They speak of Star Wars as the older generations speak about the Sagas, there they find all their “mythology”, “poetry” and cultural references. It’s so sad. And every fifth

word they use is American jargon. And my generation? The only book we read is Facebook.

I know that this is a truly global shift. I think we can call it a spiritual climate change. But it’s of course riskiest for us, the small nations. (As for now there are only 330 thousand people living in Iceland. That’s like the city of Leiceister.) We really have to be careful not to lose our identity to the big multinational conglomerates. You sometimes miss the good old days when the biggest threats to our culture were considered to be Alistair MacLean, James Bond and Led Zeppelin.

But to the young generations I probably sound like my parents sounded to me. Back then the saying was: “You’re watching television all night long. How about reading a book?”

Today it is (I have actually overheard myself saying this to my children): “You’re playing computer games all night long. How about watching some TV?”

I guess tomorrow it will be: “You’re on this snap chat thing all night long. How about playing a decent good old computer game?”

An Irish Situation?

During the dark and cold ages of stinky turf huts and general stagnation, when we were a Danish colony, Icelandic culture survived on literature. The Edda and the Sagas. Those things were the main reason we did not loose our language. Curiously enough, even the Danes sensed its value, and did not try to have us speak Danish, like they did with the Norwegians. (Tak så meget for det.) They did not wipe out our culture like the English did with the Irish. For an Icelander to visit Ireland is almost heartbreaking; you can not help but wonder how things would be if the Irish language had prevailed. (Not forgetting the humiliation of naming the London-Dublin route a “domestic flight”.) Here the Irish suffered from their geographical closeness

to England. (And maybe this also goes for Scotland.) In our case it took a whole week to reach our shores, the distance also saved us. Plus the cold. Icelandic culture was kept in the freezer for a thousand years, that’s why we managed to preserve it.

But now it’s on the table, thawing. Those Marvel Vikings keep raiding our heritage on a daily basis. So we better watch out. If we swap the Sagas for Star Wars and Icelandic for English, we might end up like the Irish.

The American Post War Influence

We have faced this problem before. When the American Influence of the fifties and sixties was at its peak, the Icelandic intelligentsia declared a cultural emergency and during all my childhood the battle was fought, against American TV, American food, American music, American slang, American candy. I mean, I did not get to eat a hamburger, until I was thirteen and came to the States, and Coca Cola was considered the drink of the devil. (We actually lost this food battle… burger, fries and coca cola has been our national dish for decades now.)

We even set up a special committee that was assigned to come up with an Icelandic word for each new thing America gave us. Therefore, in our language telephone is sími, television is sjónvarp and weekend is helgi. This tradition lived on up to the eighties and nineties, when we found our own word for computer: tölva, an ancient word from the Sagas closely related to völva, the sybil that could see the future. Tölva is sort of the sibyl that knows all the numbers. And soon after, laptop became fartölva, a mobile computer. But this battle we seem to have lost by now. For two decades we have used the verb að downloada (to downlode) and in Icelandic an app is an app, hip and cool is hipp og kúl, and woke is woke.

“I don’t know. It’s a mystery.”

But again to our literature. How did it come about? Why did some farmers in Iceland write the histories of the Norwegian kings and the first European novels? This is the million dollar question of course, and the obvious answer would be the one that the theatre monger, played by Goffrey Rush in the movie “Shakespeare in Love”, mutters when under pressure:

“I don’t know. It’s a mystery.”

Well, the mystery contains many factors. The excitement in finding a new land and occupying it is always a great setting for stories. And then there was also a meeting of cultures. The official version is that Iceland was populated by Norwegian Vikings. Those guys were, however, all over the place (for example: when you read the Sagas you always have someone who gets lost at sea and ends up in a foggy fjord in Scotland, or another one who makes a nice stopover at the court of the king of the Orkney Islands.) Many of the Norwegians took Irish slaves or Irish wives, so that a good part of the early Icelandic nation was of Celtic origin. Some words in Icelandic, names of people and places, are clearly Celtic, and recently scientists have claimed that 30% of our genes are Irish. And most likely the writing culture came with them; the Vikings had the stories and the Celts knew how to write them. At least my impression is that even today Icelandic literature is a bit different from the Scandinavian one, not as realistic, not as somber, and a bit more crazy. I sometimes say that Icelandic literature is like Hamsun gone Wilde… Oscar Wilde, that is.

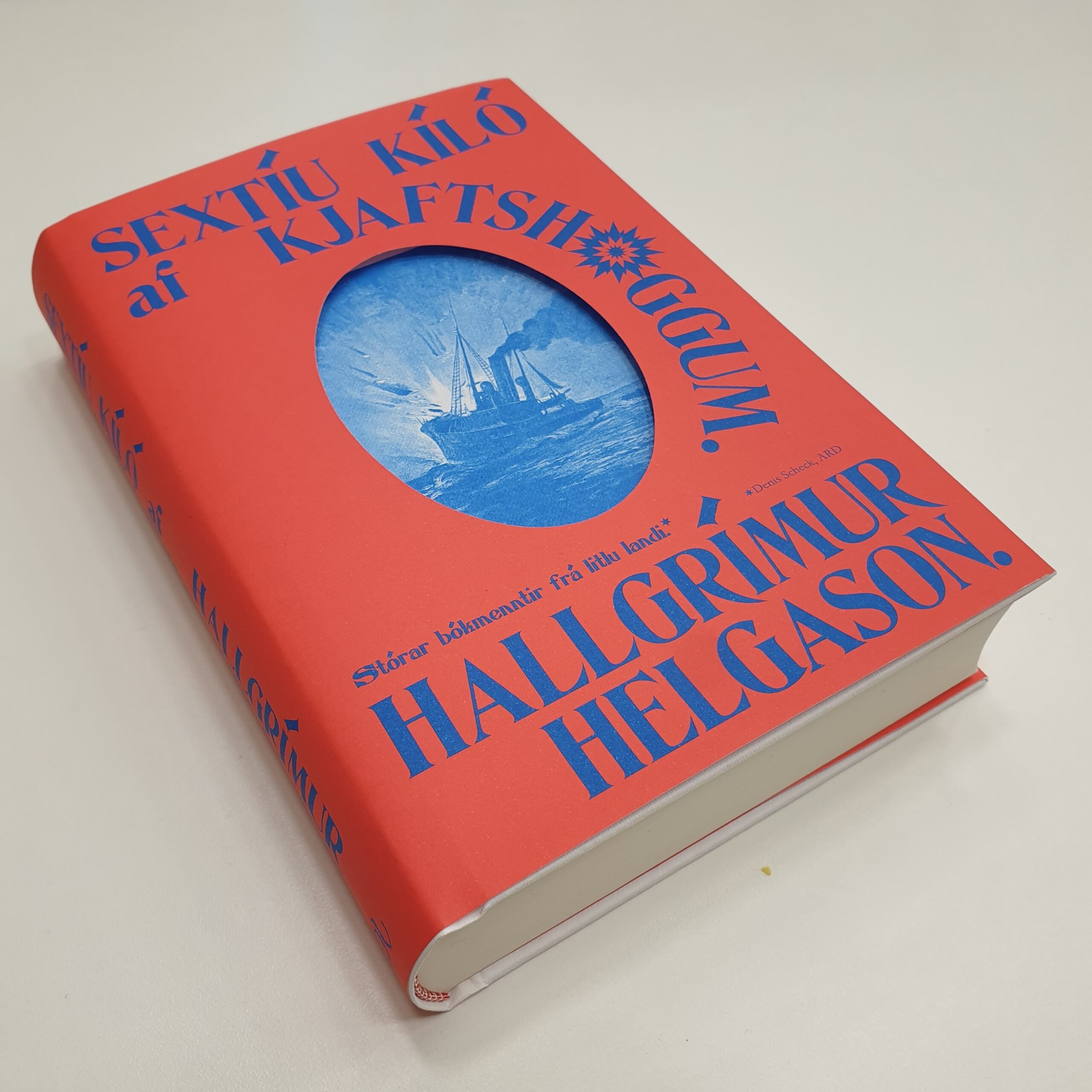

And to give you an example of that, I will now read another short chapter from my Woman at 1,000 Degrees.

Woman at 1,000 Degrees

“The Woman at 1,000 Degrees” is the story of an eighty year old woman who lives in a garage in Reykjavik along with her laptop computer and an old German hand grenade from the Second World War. She is bedridden with lung disease and has chosen to rent this garage because she neither has a family to live with nor can she stay in an institution because she doesn’t want to give up smoking.

It’s based on a true story, a woman who was the granddaughter of our first president and had a father who left her to fight with Hitler in World War 2. I never actually met her, and I did not know anything about her, until I was helping my ex-wife in her election campaign. I went down to the headquarters of the Social Democrats were they handed me a random list of telephone numbers and asked me to call them, asking people to vote for the Social Democratic Party. And number three on this list was this old lady who was living in a garage and started by telling me flat out:

“No. I’m not going to vote for those fucking communists”.

This was interesting enough for the writer in me, and I stayed on the phone with her for the next hour and totally forgot about the election campaign. She was so interesting, this old lady, so clever and full of wit. She told me all about her life in the garage, how she was always online and was even running her own language school, teaching Icelandic to people in Argentina, Malaysia and elsewhere. After I hung up, I thought about her for a long time, thinking I could maybe write a novel about an old lady in a garage. But when I finally tried to visit her, I sadly found out that she had passed away. But I found out who she was, a semi-celebrity in her day, known for her humour and hard-drinking. So I did a lot of research and wrote this novel. Here she is, in her garage bed, calling the local crematorium.

Leave A Comment